In the world of conservation, leadership positions have been dominated by men for generations. But two powerhouse female conservationists from Africa, Dr. Leela Hazzah and Dr. Colleen Begg are on a mission to change that. They co-founded Women for the Environment Africa (WE Africa) with a Leadership Council of eight African women conservation leaders intending to restore balance within environmental leadership.Through WE Africa, female conservationists are given access to a range of leadership building opportunities, including tailored trainings, one-on-one coaching and mentoring, community building, peer support, and increased visibility. Leela and Colleen share, with Damaris Agweyu, their motivation for embarking on a mission to help female conservationists in Africa rise, be counted and effect positive change.What problem is WE Africa addressing?

Colleen: African conservation suffers from a profound imbalance in leadership where women occupy less than 5% of the top positions. And yet, with the crises of loss of diversity and climate change, we are at a moment in time when courageous, compassionate leadership is urgently needed. We recognise that if we can have better leadership- leadership that is inclusive and diverse- we will create greater impact in our environmental work.

Leela: The sense of loneliness of being the only woman at decision-making meetings became increasingly frustrating. This brought about the idea of WE Africa, where we said, let's put women at the heart of transforming the environmental movement on the continent. When we started sharing our frustrations regarding the status quo, more and more women started coming out of the woodwork; this is a real problem.

There are simply not enough African female role models in the environmental space. If you ask anyone which women are well known in this space, they'll tell you, Jane Goodall. Yes, she has done tremendous work, but she is not African and has hardly spent time on the continent. Wangari Maathai occasionally comes up, but the point is, women are just not visible and yet there are so many who are doing amazing things. We thought, is there a way to make them more visible and, at the same time, create a greater impact on our environment?

We believe that if we can empower the women at the top, they can empower the ones coming after them. There is a sense of urgency in what we are trying to achieve because when it comes to creating the necessary impact, we don't have the luxury of time.

On a personal level, why was it important that you start WE Africa?

Colleen: This is an opportunity for me to pay it forward. I'm 52 years old and have been working in conservation for 30 years. I want to make the kind of contribution that ensures that other women coming after me don't necessarily have to face the same challenges that I did. I am so tired and frustrated with conservation at the moment that I don't see how we solve our present-day crises if we don't do things differently. This is my opportunity to create impact as an individual so that when I'm 90 and looking back, I don't ask myself why didn't I do more.

Leela: I believe the gift of frustration is that it brings about change. You wouldn't change something if you weren't frustrated, right? We've been in this space for a long time, and now I know for sure that we aren't doing things well enough. We're losing species and important habitats at an alarming rate. And it all comes down to the way people lead, the egos, the lack of sharing, the need to get credit for things. These ways of leading are not working, and we believe we can change that.

Colleen: To speak a little about the trainings we offer, there are many leadership courses out there, but the problem is that many are western-based. We need courses that are tailored to African experiences; we live and lead differently here. Even if we have some of the delivery team bringing their ideas from outside the continent, we still need to have content that is relevant to what we deal with on a day-to-day basis.

I have enormous white privilege, having grown up in South Africa. But, we also need to understand what it means to be a black African woman in the environmental space. And for that, we need to take the lessons learned from everywhere else, bring them to Africa and make sure we create what we call a "round room". This way, African leaders can co-create their experiences and learnings and find what they need to thrive in their leadership spaces.

The thing that the environmental movement needs more than anything is innovative ideas.CLICK TO TWEETWhy do you believe that female leaders, in particular, are equipped to handle the environmental crises we face today?

Colleen: It's not specifically women, but diversity in a team that is critical. If you only have men, white men particularly, making the decisions, then there is a lack of diversity in ideas. And the thing that the environmental movement needs more than anything is innovative ideas. You can't get that if you all look the same, speak the same language or come from the same background, that's the first point.

The second point is, I think that women in particular, have a legacy mindset. They are often more collaborative and can be very empathetic. This is what we call courageous, compassionate leadership, and it's lacking in this space. I'll give you an example: I work in a place that lost 10 thousand elephants in 10 years. It was absolutely heartbreaking, and yet I went into so many meetings where nobody showed any emotion at all; everybody was just counting the numbers. This really bothered me.

One day, I got some excellent advice from Christiana Figueres, who was one of the elders on the Homeward Bound leadership experience. Christiana led the process to rebuild the global climate change negotiation that led to the historical 2015 Paris Agreement. Amongst many nuggets of leadership advice, she said, "You can cry. You can cry when things are emotional and you feel deeply about them, but you have to finish your sentence." That was so powerful for me. What I got from it is that you have to be able to lead and have these conversations, but you don't have to suppress all the emotion that comes with it. Christiana's advice gave me permission to be emotional about some of the horrible things that are happening.

Women need to bring their emotions, compassion, empathy and their legacy mindset to the environmental space.

So it's a case of bringing different voices to the conversation?

Leela: That's extremely important. We are not saying we only want women's voices, but when we have less than 5% women at the top, then we clearly have a problem. If we believe in inclusion, which we deeply believe in as a core value, then we need more women.

Another vital point to make is that when we talk about inclusivity and having diverse voices, it's not just in regards to gender. It's also about race, education levels. Colleen and I both work very closely with local indigenous communities, of which 80 to 90% have never been to school. We want to get enough of those voices into the decision-making arena.

And when it comes to women, I agree, they tend to be more collaborative and compassionate in their approach. If you look at the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, women leaders have outperformed men hands down in terms of how they have handled things. I don't think the question is: Are women good leaders? We know we are good leaders; it's more that we just need opportunities to lead.

Our 12-month WE leadership program is all about getting to know yourself, believing in yourself, and knowing that your ability is enough. You're not trying to be like a man or somebody else. Just be authentic, lead with your values, make sure you are looking out for others and bringing them along with you on the journey. We are all about changing leadership norms that have been stifling us for generations. We believe that if there are enough of us doing this- leading differently- we'll start seeing the change.

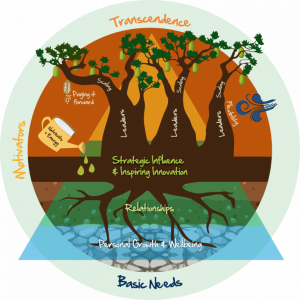

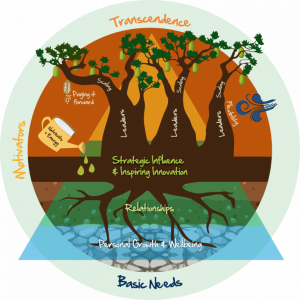

WE Africa's Leadership Experience:CONCEPTUAL MODEL

WE Africa's Leadership Experience:CONCEPTUAL MODELWe can see more and more women rising to the top with each passing day, but as a consequence, there's been this backlash that makes it all seem like a battle of the sexes. Can you speak to this?

Colleen: I obviously don't think women are perfect. Sometimes we create this "war" because we are so frustrated and are feeling so powerless. Remember, we are functioning in a system that was developed by men and for men; it's tough to push your agenda through when whole systems have been created to serve one gender. I think sometimes we come across as more strident against men than we really are.

We had a conversation through WE Africa with Everjoice Win, a formidable feminist from Zimbabwe, who said something interesting. I asked her whether she thought feminism in Africa was different to the western kind of feminism. She said (to paraphrase) that all types of feminism are shaped by our particular circumstances and stories. She said that while some individualistic styles of feminism come from a capitalist model of organization, Africa feminism is about collectives and about uplifting each other as a collective as that is what women do.

As we move forward, I would say to all the men who are angry that we need to start giving women voices and in the environmental space particularly. It is about balancing this aggressive and often militarized form of conservation with a softer, more feminine side. This doesn't necessarily mean it has to be led by a woman. In my organisation, I have a male Director who is very compassionate in the way he leads; it's the form of leadership and

not the gender of the person that counts. Incidentally, it is women who tend to have that compassion and empathy that is so desperately needed.

Leela: Part of this is creating safe spaces for people to share why they are feeling this way. I have a lot of these conversations with men, particularly Maasai men. Do they feel excluded? How do they feel when we are having these conversations? Because I am very aware of all this. Colleen can tell you that I tend to include too many people, and then we're in chaos because you just can't include everyone all the time.

I find that when I'm having these conversations with somebody I trust, and they trust me, we can genuinely unpack why they are feeling a certain way. It is so much healthier. Resentment builds up when there's a lack of communication or safe space to unpack why people may feel the way they feel.

If the men are saying, "Well, I got passed over, and a woman got the job because they are saying they want more diversity", then it comes down to us trying to understand the situation. And here is the situation: There are lots and lots of men at the top. But it's not about excluding them. It's about asking them to champion the cause with us. Because this is not just a women's cause, it's our collective cause. The science points to diversity being necessary for everyone to have better outcomes. Change is scary, but when you think back on it, you realise you've been stressed this whole time, but it wasn't so bad after all. It's about figuring out how to do it in a safe and productive way.

Colleen: I've actually had quite a lot of pushback from women who say, why is this a woman-only group? Women get pretty defensive about it because they feel that it almost makes it worse. But I think there's no doubt that women battle to have some of these really personal conversations if they don't feel the space is safe. There's something about an all-woman group, when it's set up the right way, that creates the space for them to have really open conversations and create change in their own lives. I don't think it would be possible to have the conversations we're having in a mixed group. Not at this point, but I hope we can get there.

Staying on the subject of inclusivity and diversity, why is the conservation space dominated by white faces?

Colleen: Several issues: the first is this perception that conservation is so badly paid, and it requires so much sacrifice that only people who have support from their own families can do it. For that matter, it is not necessarily attracting the best, most talented minds. When I look at my background, I had an opportunity to do it; there is definitely the element of privilege in it.

There's also an element of lack of visibility for black conservation leaders. When we are looking to raise money, we tend to turn to the west, a place that's dominated by white people. They, in turn, identify with the white conservationists in Africa, they live vicariously through us. They donate money to a "conservation hero" to "save Africa" thus perpetuating this myth that black African conservationists don't exist and that conservation is about individuals rather than teams. But there are plenty of black conservationists here, they just don't have the visibility that they deserve on these platforms; that's something we are looking to change.

I think it all comes down to racism in conservation. I think that conservation is the last example of a lack of transformation. When you look where the money is going, the panels, boards, the people leading conservation organisations in Southern Africa, the lack of diversity is appalling. We have to change that because many incredible black conservationists are just battling to push through the system.

Leela: If we don't have an intentioned way to provide visibility or safe spaces to share stories and exchange ideas, people will keep seeing the white people that are running the programs. The question then becomes; can we push this in a direction that provides visibility to people where it matters? Because when there are enough African women getting enough visibility, people will start to recognise that it doesn't always have to be a white man who is leading all the efforts.

Colleen: We also need to get out of the way. When there's an opportunity to be heard, let's take the spotlight away from us and give it to someone else. I think that's an enormous barrier, and too few people are talking about it.

I was on a panel conference in Kenya where Resson Kantai Duff from Ewaso Lions organised a panel on

white privilege and racism in conservation. She battled to find white African conservationists who were prepared to say that they had white privilege. I am perfectly happy to do it, but the point is, there are so many white people that either deny it, get defensive or are scared of saying it; maybe because they are afraid of losing their positions.

I recognise that I'm imperfect when I have these conversations because I come with so much bias and there is a vulnerability in these conversations. It is scary. I know that I sometimes mess up; I may very well be offending you now and not know it because I have a whole lot of bias that I can't even see most of the time. But if we're not prepared to put ourselves out there and say, "I recognise there's a problem, I recognise there's racism in conservation, I am imperfect, and I know that I am privileged", then how will things ever change?

This is why we need safe spaces to talk openly about what the problems are and how to move forward. Through the WE talks, we want people to feel safe enough to call Leela and I out on some of these things. We want them to feel confident to have these conversations in their teams and circles, and then, hopefully, we can start seeing some change.

Leela: This is something I've been thinking about more and more. We keep talking about safe spaces. These are words people use, but what do they

really mean? Yesterday we spent 2 hours getting feedback on WE Africa, and I'll tell you, life-changing things are happening with these women. It's incredible. A lot of it has to do with the safe space we have been able to provide. This is a place where you can come and be you with no judgement from anyone. You can shine as you are, even with your imperfections. We didn't over-engineer the concept. We just provided the right people in the right space. That is the heart of WE talk; a safe space where people can be vulnerable, a space where they can connect and be heard, even when it comes to difficult topics. You can never do any of these things if you don't feel like you're in a safe space.

It's about normalising the difficult conversations, in a sense.

Colleen: It is. Just like we are doing now. That way, it's not always risky. I mean, it's ridiculous how defensive people get when it comes to the subject of racism!

We are self-aware, but we still make mistakes. One of the things I wish for WE fellows is that they can talk about what is happening in conservation and how we change things because there's no point in just recognising the problems; we need to also do something about it.

In some ways, it's similar to the Black Lives Matter Movement, but it's a little different here because we are in countries that are led by people with a colonial back pinning, and we are still struggling to get past that. South Africa is still battling to get past Apartheid. I think it's almost worse than the Black Lives Matter Movement because here, it's so hidden, and I'll give you an example: I often go into meetings with black government officials, and someone will say something like, where is the person who can make the decisions? This is directed to our conservation director, who has the same power we have. What the government official means is:

Where is the white person? It's so it's entrenched in the way people frame it and the way people see conservation organisations. It's this horrible thing that we have to get past in conservation.

You are both phenomenal women, obviously. What are some of the life experiences that shaped the people you have become today?

Leela: I had a very strong grandmother- that always helps. I had 2 Muslim Egyptian parents, and in this case, women are not usually heard. When we had family gatherings, I always spoke up. And my grandma was constantly saying, "Just let Leela speak; she has something to say". She validated my voice from a very young age, and that was really helpful for me.

My parents didn't have the money to send me to university, so they were like, you better be smart and get a scholarship. That was actually good because then I had to hustle hard. I started so many businesses and was constantly innovating and re-inventing myself. I sold mangoes on the side of the road, DJ'd dancehall reggae for a radio station and learned how to fix computers. I had to convince people that I was good at fixing computers in order to make money to pay for my tuition; I did whatever it took.

I don't regret any of those experiences because they helped me get to where I am now. I've always known what I wanted to do, so I am grateful to have this position of privilege today where I can spend my time doing things I love and giving back in ways that I can. I have figured out who I am and what I'm about, and that's a great feeling.

Colleen: I feel the same way, like I am finally finding my voice and growing into me. It feels very late, but I now have a better sense of who I am.

My experience was different to Leela's because I grew up in South Africa. When I went to university in South Africa, I was utterly clueless about the history of South Africa. I'd gone to a government school, but we didn't learn about what was actually happening in the country. It was when I hit university at 18 that I realised how completely naïve I'd been. Still, there is no excuse for how ignorant I was.

At the university, there was a lot of rioting and protesting at the time, as it was just before Mandela was released from prison, and I remember my father saying to me, "Do not get arrested", because he knew my activism spirit. I don't think he realised how overwhelming it was to suddenly realise that everything you thought you knew was wrong- a lie. It was a huge deal, and I've been grappling with that along the way, trying to unpack all the privilege and bias I've had.

I've been running a program in Mozambique where 60 thousand people are living inside a protected area. More than anything else, it's been about listening and trying to understand how you make this work with people who are so deeply connected to their land. This is in total contradiction to the fortress` type conservation I grew up knowing: kick the people out, but the fence up; that's how conservation works. But in Mozambique, it's the complete opposite. From my experience in Mozambique, I feel like the only hope we have is to include everybody in the conversation. This has been a journey of learning and unlearning.

I suffer a lot from

imposter syndrome, so I always feel like I'm going to be found out to be a fraud. But that insecurity in me has its positive side in that it helps me become very aware of how much I still have to understand about what it means to be African, what it means to lead in these environments, and how privileged I am. I feel like WE Africa is an opportunity for me to learn even more and hopefully allow me to give back in the process.

I am hoping my children can do better, and we can stop this racism and cluelessness that goes on, particularly in South Africa. I love South Africa, but it's a dysfunctional place.

Read the full interview on Qazini  WE Africa's Leadership Experience:CONCEPTUAL MODEL

WE Africa's Leadership Experience:CONCEPTUAL MODEL